ANTE mag is proud to shine a spotlight on the dedicated artists who are exerting an impact in the arts as we move into 2021. From ongoing or upcoming solo exhibitions to gaining recognition through artist talks, honors, appointments and prestigious residencies, these are some of the top artists we have an eye on as we move further into 2021.

Here we present, last but not least, our final cohort of artists in the 21 for 2021 feature. Each artist has images included with their respective coverage below, but be sure to click through to their websites – linked through their name in the header – to view more of their practice and familiarize yourself with your favorites!

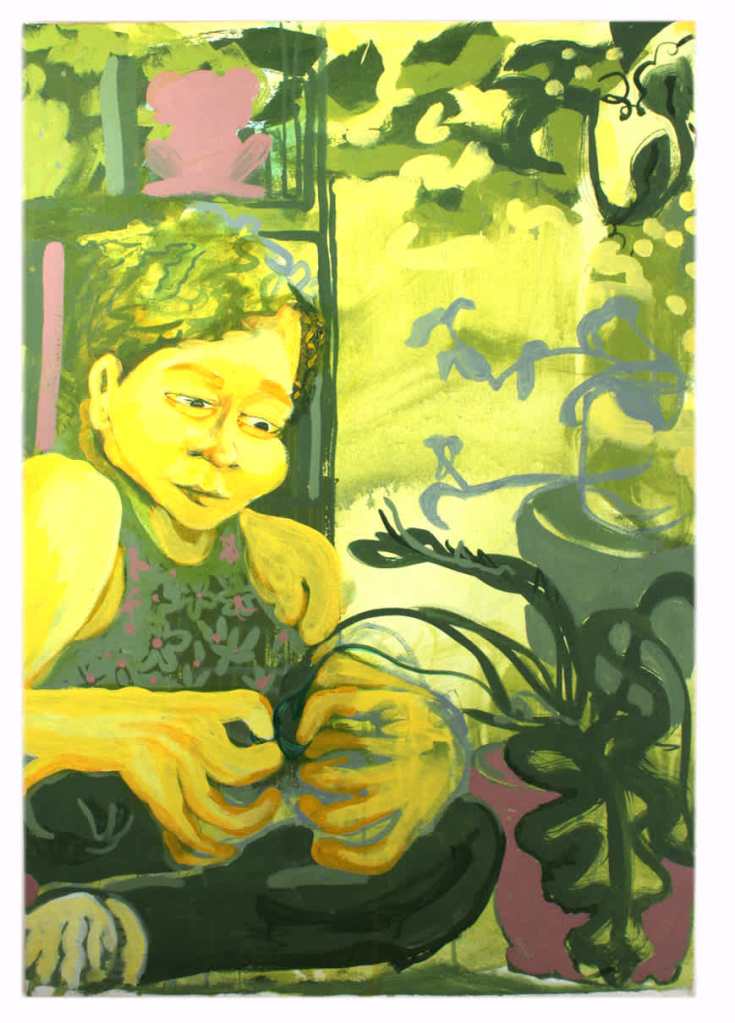

Lead image: trade:gene, Acrylic, screenprint, oil pastel, colored pencil, collage, and puff paint on canvas and paper, 32 x 33 1/2″ (2020) Image courtesy artist Neil Daigle-Orians.

Lives and works in Brooklyn, NY – by way of Newark, NJ

ANTE mag. 2020 marked your solo show with Arcade Project Curatorial, Rainbow Country, at Paradice Palase. Congratulations on this milestone! Can you offer some reflections on that experience?

KD. Thank you. I had just moved from Newark to Brooklyn after living in Newark for a very long time. The solo offering in spite of the pandemic summer was extremely encouraging. It was early in the pandemic so we were one of the few galleries in New York to open a live exhibit meaning we had to figure out the guidelines for engagement without much example. We also had no idea if people would come, who would come or how to follow up the opening. Fortunately, the show was well received and got some great press. It was a pleasure working with Arcade Project and Paradice Palase on that show. Rainbow Country was pop art, a mash-up between Caribbean and American culture longing for a 70s approach to traditionalism while revisiting our post-WW2 origins. Its narrative is a fantasy, not expected to be complete or make sense, told through something we hoped to see: A Caribbean comic-book! I never saw the series as a look at race, it barely makes it visible. It was quite interesting to see how it was interpreted as the BLM protests happened.

ANTE mag. Can you talk to us about your Artist/Muse series, which was featured by Ground Floor gallery in Brooklyn?

KD. So the Artist/Muse series I updated to Selfie World and it is my current work. I became interested in vernacular digital photography as source material and how it shapes the way we experience sex, desire and intimacy. I work in small intimate watercolors. If I find something problematic I complicate it. At times the body is located in multiple places as in Her Window My Window. Other times I use the watercolors to revisit the casual capture of the photograph as in The Visitor where you find an air of caution and discomfort given the current climate. I have much of this series done and will continue to work on it as is but this year I hope to move on to canvas. I also began work on a relational performance piece for it.

ANTE mag. How has the past year allowed you to focus on creating new work in your studio?

KD. Just working on new pieces. I spent my days scanning and preparing for opportunities. I haven’t watched any online exhibits. I had never applied for a grant before but in 2020 I won a few which helped me to ready more work. When the year was a grind at times I broke it up by pulling records for my weekly DJ set. I still managed to meet some great people and make some good contacts who are ready to collaborate.

ANTE mag.What do you have on the horizon in 2021 that you can share with us?

KD. I was gifted a temporary space and set up an installation of my new work where I host private viewings. Offerings include a figurative group show and a public art piece but with Biden now as President maybe things will get moving.

Lives and works in New York City

ANTE mag.Can you introduce us to the mediums you work within? Would you call yourself an interdisciplinary artist?

JK. It’s useful to think of my work as a series of projects that each incorporate whole constellations of objects, performances, videos, websites, etc. I start by researching and writing short essays that pull from many places: scientific journals, historical accounts, autobiographical reflections, etc. Once that is finished, I begin to think about what kind of artworks best communicate the essay’s sentiment.

For example, I began my upcoming exhibition, How The West Was Won, at Rockford Art Museum, by writing out a historical timeline like something you might see in an archeology museum. I traced the North American continent from its geological formation as Pangea to the recent Trump administration. It was a thought experiment, charting a relationship between geological time, colonialism, white supremacy, and golf. The exhibition will feature sculptures that look like archeological golf remains, prints, and an immersive three-channel, superwide-format video that I shot in California. For the video, I brought two older white Trump supporters out to the Mojave Desert and asked them to play an ad-hock feral-style golf game across the landscape. A website accompanies the show, where you can buy a baseball cap that I designed.

ANTE mag. Talk to us about how your work involves the audience as participant: how did this become a factor in your work and in what ways do you seek to implicate the viewer?

JK. I am interested in bodies, identity, and landscape. When you look closely, the distinction between a person and their surrounding ecology is very diffuse. Focusing on this destabilizes cultural beliefs that separate us, delineate identity groups, and construct an artificial separation from nature. I want to bring viewers into the process of exploring this collectively.

For example, In Bodies Of Water, an exhibition/ theatre performance in 2019 at Dublin Fringe Festival, an audience was invited to an exhibition’s opening night. The exhibition was supposedly by an artist who had disappeared at sea a decade ago. The curator, the artist’s assistant, leads the audience through the video works displayed. As she goes, both the exhibition itself and the curator’s emotional state fall apart. She shares the weight of her grief with the audience for a relationship that never gained closure. As the entire experience’s fictional nature becomes increasingly apparent to the audience, the artist becomes an avatar for sorrow and the ocean, surrounding the audience through video projections, a metaphor for loss and the unknown. In cases like this, I think a lot about the viewer’s bodily relationship to screens and objects on display. I think of an exhibition as a performance score guiding the audience through a complete experience.

In All My Friends Are In The Cloud, the show centers on an ever-expanding digital archive viewed via a pillar of monitors. Images of people embracing gently spin and scroll upward like video clips in a social media feed. As the images ascend, they unfurl into a whirl of digital fragments. By the time each embrace reaches the top of the screen, its image has disintegrated completely. Viewers coming to the gallery enact the embraces in a separate chamber. Through a real-time 3D scanning system, they see their own likenesses ascend, unfurl, and disintegrate.

ANTE. Can you speak more on how your background impacts your practice and frames the type of work you create?

JK. My mom was an archeologist. As a teen, I would work on digs in the Irish countryside, Stone Age burial chambers, and religious sites four or five thousand years old. I loved to imagine the communities that once lived there across those great breaths of time. I was struck by how completely different their worlds were despite sharing the same territory. Ireland itself is a country characterized by centuries of colonialism and territorial warfare premised on layers of opposing belief systems.

ANTE. What are you looking forward to in 2021 in your studio?

JK. I’m about to open my first solo museum show at the Rockford Art Museum in Illinois this February*. It’s a large hall that I am filling with sandcastles, relic-like sculptures made from golf equipment, and an immersive video. The title, How the West was Won, is shared with the 1962 ultra-widescreen American western film, which opens with this narration: “This land has a name today and is marked on maps. But the names and the marks and the land all had to be won. Won from nature and from primitive man”. This unnerving quote about westward expansion contextualizes the entire exhibition. The two men I invited to participate are stand-ins for pioneer cowboys. They are like two ghosts, forever destined to haunt the barren landscape, not with rattling chains, but with swinging golf clubs.

*Editor’s note: King’s solo show at the Rockford Art Museum opens Feb 14th; more info: How The West Was Won – Rockford Museum of Art

Lives and works in Connecticut

ANTE. Tell us more about your practice as an artist – how do you conceptually seek to break down boundaries between mediums in your work and engage with the viewer/participant?

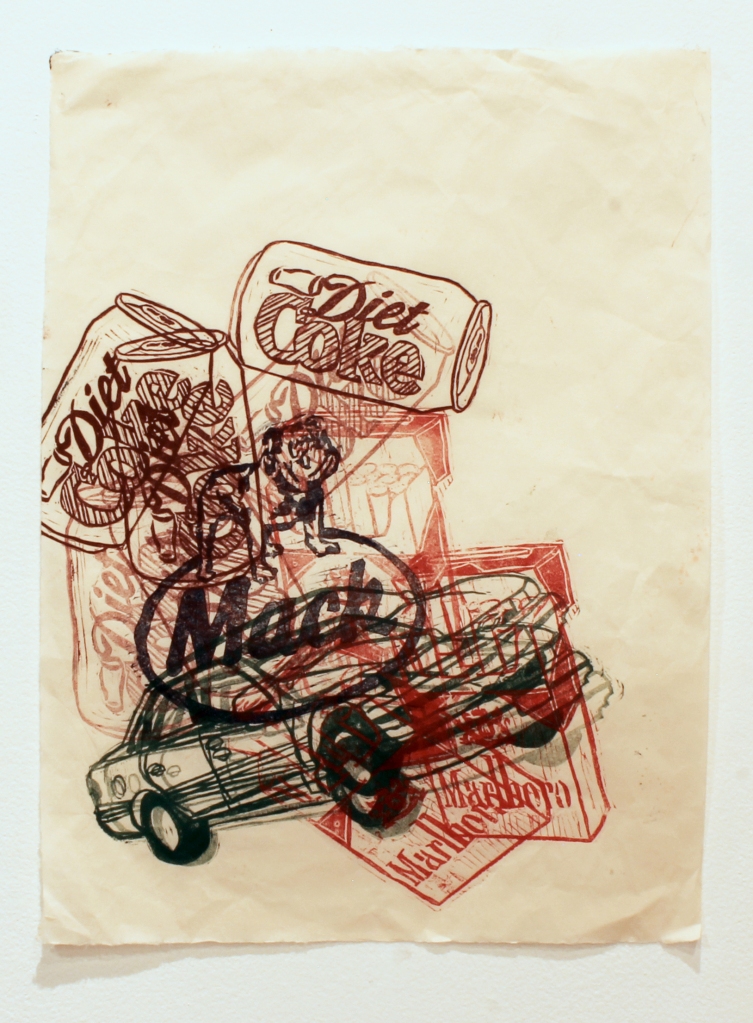

NDO. Before embarking on a project / making a thing, I always have to undergo a self-imposed existential crisis. Something I realized during grad school is that medium plays an important role in my work in that I have this need to conceptually tie the object/thing to the materials/medium. I have to ask myself; why this process? Why this thing? Why this medium? I have to justify the process and the object to make sense with the final product. As a printmaker, I often connect to the history of the process as well as the relationship we have with printed materials. Print media has a sense of authority in our world (publications/books, news/magazines, etc.) but often require a human hand to give power (checks, legal documents, etc.) I make a lot of zines and other books to connect with the intimate practice of journaling or diary keeping. I like to use plastics and other synthetic materials when discussing mental health and pharmaceuticals, sort of a metaphor surrounding the synthetic nature of my serotonin. Materiality and process have an equal role in the conceptual process as aesthetics do, so in spite of the chaotic nature of my work, I try to have meaning behind what I’m putting together and why.

ANTE. Your performance for Home Room, you mentioned, was a new direction in an ongoing series, can you tell us more about the genesis of Whin(e) and Pain(t)?

NDO. In 2018, I was commissioned by Artspace New Haven to create CONVERSION THERAPY, a site-responsive installation and performance in the former presidential suite of the Bayer headquarters. The installation included a series of performances called “Micro-Group Therapy”, where I engaged the public in a 12-step manual of my own creation. This led to me reconsidering how my practice could/should focus less on object making and more on creating spaces and experiences.

In February of 2020, I embarked on a project called A LITERAL FIRE SALE. It was an attempt to cleanse myself of my previous works and projects to start anew. I listed most everything I could catalogue of my previous work on my website, especially undergrad and graduate work, and anything that didn’t sell I destroyed during a performance called ritual for a phoenix. The intent was to restart my practice focusing on social practice, performance, and directly engaging an audience in my installations. And then the pandemic hit, and suddenly there was no longer a social with which to engage.

Whin(e) and Pain(t) was one of the projects I had started working towards producing after ritual. At the time I had access to a nice studio space and even larger performance space, and wanted to create performative engagements with groups of people using process-oriented making as a ritualistic group therapy. But like my other work (and life, let’s be real,) humor is used as a coping mechanism, so exaggerated performative actions were necessary. When the pandemic hit, I was furloughed and had a lot more time on my hands, so I started making weird little performances streamed through Twitch. One of them, The JOY of PAIN(ting), was sort of a way to explore the ideas of Whin(e) and Pain(t) by myself in my basement. Home Room allowed me to reconsider how this project could exist — I’ve long been fascinated with YouTube as a platform and have been wanting to create YouTube-specific projects, so I think this will be the next step in this project.

ANTE. How has working from home during 2020’s quarantine improved or detracted from your practice?

NDO. Weirdly enough, especially in this latter half, quarantine has forced me to focus on what I actually want to make as opposed to what I think will get me attention or boost my career. I have a full-time job in curating and arts administration at a contemporary space, and as a result I’m often filtering my own work through our own programming — what will get us a grant, what work is interesting but undiscovered, etc. Sort of like an internal dialogue of if this was displayed at my day job, what kind of critical attention could I get for it? This has been limiting in a very unfortunate way, but quarantine forced a shift in priorities.

Since October, I’ve started returning to my roots with a project focused on exploring my posthumous relationship with my estranged father, leading me to creative problem solving in terms of process and technique, and I really love the work I’ve been making in this project. And the funny thing is, as I focus on what I want to make more, I think I’m making work that better fits into the unnecessary, self imposed filter.

ANTE. What are you looking forward to in 2021 in your studio?

NDO. I’ve recently been researching how to make paper using plants and harvest clay from riverbeds. I’m hoping to connect with the current residents of the houses I lived in during my childhood in Mount Prospect, Illinois and Omaha, Nebraska to collect plants and clay to create a series of works about my disruptive childhood, sense of identity, and how I came upon my queer identity. I’m hoping the current owners of these respective properties will be understanding of the ridiculous nature of my ask, however hopefully including return postage and containers I’ll be able to convince them further. I’m hopefully going to receive some travel assistance and/or residency that will help me collect the clay myself to then create vessels and other objects in addition to the paper-based works.

Utilizing materials directly tied to the places these events occurred, I’m interested in further pushing just how conceptually tied my materials can become to the objects themselves. My work about my father, patre in absentia, is a further attempt to connect with my past and ancestry through various ritualistic mourning practices, both historical and of my own creation.

It’s funny — I didn’t think of it until now, but I’m very invested in exploring my history right now as a means to further understand my contemporary sense of self

Lives and works in Queens, NY

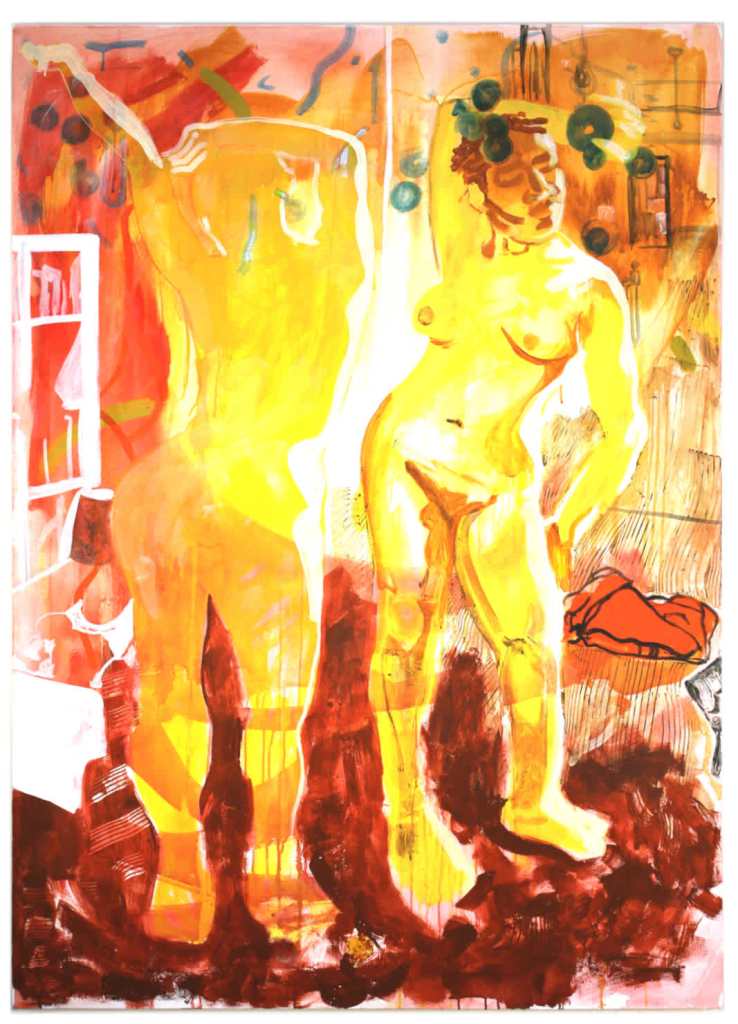

ANTE mag. Tell us more about your career this year: you had a solo show at the gallery Art of This Century, along with participating in other exhibitions. Reflecting back, what were you proud to accomplish in 2020?

KPM. Overall, I am proud that I kept moving through 2020. There is so much to be proud of. Besides the solo, I am proud of my work at Uprise Art Gallery. All the work in online shows, I am proud of the show I curated at Olympia in the summer, I am proud of writing about Joel Adas in Hyperallergic for Artists Quarantine With Their Art Collections by Stephanie Maine. I’m proud of putting pieces in Along the M Train at The Yard, Williamsburg Bridge with ANTE that were truly the first things I made in lockdown. And I am proud of the way my community came together.

ANTE mag. Talk to us about your practice over the past year: how has your process, and the imagery present in your paintings, shifted in response to the pandemic?

KPM. I went from drawing from observation in cafes to drawing plants in window and imagery scenes. I began painting emotional responses to missing my friends and family. I made a painting of a bicyclist drifting away from a car crash, A woman cutting a dead leaf from a plant using them both as veiled ways to talk about the tragedy. I had paper all over my living room floor, I was paintings shapes of color on them.

Then more cycling paintings came and I was really doubling down on a feeling I wanted to be in my paintings last year: mindfulness, inner peace inside of the people within the painting. I needed to make paintings about that this year.

ANTE mag. In addition to your work as a painter you also function to support the artistic community in your role as part of artist-run space Underdonk in Bushwick. What can we look forward to in the space? How has your work as an artist changed in response to this role as cultural producer at Underdonk?

KPM. Underdonk is an artist-run gallery and this year we have asked ourselves a lot of big questions about what we can be and how we can serve differently. The pandemic has asked that question of alot of us. We hosted a new residency of one artist at a time in the summer and are going to do that again this winter. We have used Instagram to host fundraisers for artists when a lot of us lost work in April. Underdonk has still had physical shows, online shows, and shared artwork on Instagram to highlight individuals. We are trying out a lot of new things, and as the coronavirus spreads into uncharted waters, we will continue to evaluate our roles.

I am still getting used to the role of cultural producer as an artist. I think I have trouble connecting the two, painter and curator, but here I am. I am using both roles to achieve similar goals.

ANTE mag. What are you looking forward to in 2021 in your studio?

KPM. I am half joking when I say: I am looking forward to making a many paintings as physically possible while I am still being asked by public health officials to stay inside. I don’t consider myself an introvert but I want to paint all the time.

Lives and works in New York, NY

ANTE mag. Can you tell us about your educational background as an artist and what specific medium(s) you’ve developed in your practice?

LS. I’m an Iranian interdisciplinary artist based in New York. I received my MFA in Painting from Yale University School of Art in 2019 in New Haven, CT, and my BA in Painting from the University of Science and Culture in 2013 in Tehran. I work with hand-dyed cloth and cotton rope, acrylic paint, and poetry. My current project uses textiles and other malleable, foldable materials that may appear to have nothing to do with natural landscapes.

My work represents landscapes and interactive spaces with materials that are typically the results of agricultural productions. I aim to construct a mobile landscape in a contained physical space, where the audience feels the environment shifting. Using space as material, the connection between human and land is woven through the fibers of both textiles and imagined landscapes.

The work embodies my own recollections of various landscapes in Iran while residing in the United States’ landscape, carrying my former memories in the latter. Dwelling in between two worlds, one present and the other absent, writing and speaking two languages, drives me to think about my voice’s physicality represented as climax and base. The visual image of the frequency of my voice diagram resembles the peaks and valleys in mountain ranges. This is another reason the metaphor of the mountain is important to me.

ANTE mag. From our conversations related to your show at The Border project space, “An Absent View”, you bring the life experience you’ve accumulated into your practice and specifically into your installation for that exhibit. Can you describe how you merge the personal with the universal in your practice?

LS. My site-specific installation—influenced by Persian miniature and landscapes—contemplates the “dwelling in between two worlds,” the chasm between presence and absence. My pieces are saturated with dichotomies: physical and non-physicality, inner and outer space, weight and weightlessness, transparency and opacity, and altitude and gravity.

As an expatriate living on the east coast of the United States, I have struggled to connect to Western landscapes. In turn, I assembled an installation that is reminiscent of Tehran: “I have been carrying my memories of the mountains of Tehran, and I’m trying to recreate them.” To pay homage to my native land, I use materials imbued with cultural and symbolic profundity: my poem in Persian, “The blue sky,” large hand-dyed fabrics, and Persian hand-woven Jajims (Jajims are a type of handcrafted rug, usually woven from cotton or wool by nomad people in Iran.) tactfully construct peaks and contours with ropes and folds, a contrast to the rigid, stable structure of the Jajims that lay beneath the vibrant and playful collage of cloth. My work integrates my narrative—extractions from my subconscious—into my installation, which manifests into an expansive, dynamic reflection of an absent view.

ANTE mag. Tell us more about what recent series/body(/ies) of work(s) you’ve been focused on in the studio.

LS. My recent bodies of work include two paintings. The first one is made of hand-dyed silk and cotton cloth, found cloth, fringe, ribbon, and a dowel rod. It’s a frontal mountainous view from my memories. The Persian miniature inspires me to decide on the color, texture and making a frontal painting on a large rectangular piece of silk sewn with golden thread to the dowel rod. The Second one is acrylic paint on a wood panel. It’s based on a collage made with photographs of National Geography magazines from different times. I collected various images of different landscapes from around the world and re-created a landscape out of it. This landscape doesn’t belong to any specific place, and it’s related to the idea of Placelessness.

ANTE mag. What are you looking forward to in 2021 in your studio?

LS. I want to expand the idea of making a landscape in another landscape. The idea of an absent view is about connecting my memories with my current experience in the USA. I brought most of my materials with a suitcase from Iran, and I am creating mobile landscapes from them here in the US. This combination brings a lot of opportunities to develop in my work.

Lives and works in Brooklyn, NY

ANTE mag. Can you start by telling us about the disciplines that you work within and how you approach each medium to realize your vision as an artist?

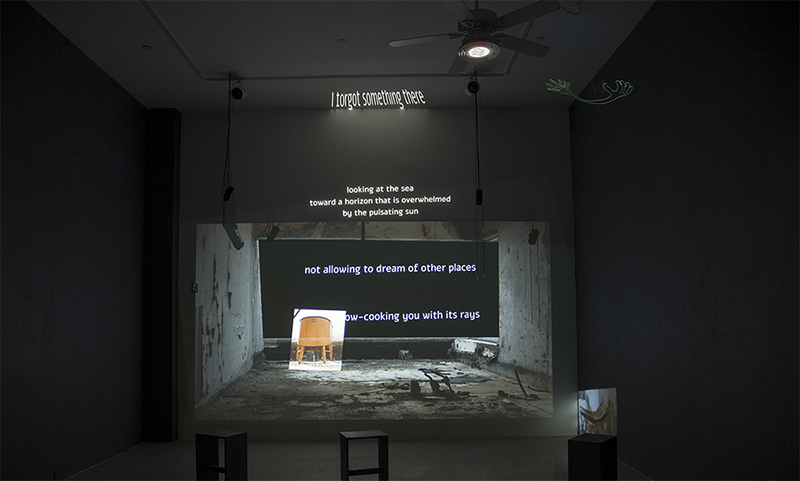

RN. I make media-installations that mash together eras, continents, and modes of consciousness. I combine video, animation, and text to describe the emotion-driven political ambiguities of our contemporary moment. My drawings and animations explore power dynamics and how we internalize systems like gender and sexuality. The characters are stuck in emotional situations of pain or desire – they dance, stretch, and contort in an attempt at metamorphosis, showing the turmoil within. In my video installations, I reconstruct and deconstruct locations I have documented, overlaying them one on top of the other or cutting holes into them to fuse together histories. My installations utilize all of these components, interacting with the architecture, reflecting off surfaces, conjuring specters.

ANTE mag. I find that often your new media work embraces aspects of the natural and built environment to speak to deeper topics about inequality in society (The Hunter (Playing Dead) and Would Have Been.) Can you provide some insight on this approach in your work?

RN. Many times the structures I document, whether in the built or natural environment, are abandoned. They allow me to think about the backdrop, about what is not being said, about the forces that dictate the way we perceive these structures and the way they orchestrate our movement around them. It allows me to engage with absence – empty spaces and place holders for unpresent bodies; empty structures that were erected to embody different ideologies that failed, creating unintentional monuments in the public space.

In “Would Have Been,” I documented a house that once stood proud overlooking fields, and now stand in its ruins, overtaken by weeds and trees. A silent witness to the depletion of the land and the exhaustion of the dominant historical narrative of Israel. My aim was to use the private story of this house to bring to the fore universal questions about borders, land, belonging, and yearning.

In a recent installation titled “How To Undermine the Horizon Line,” I explored an abandoned hotel in Israel. I documented the view out of the stripped-bare rooms, that all overlook the sea. In the video, an invisible narrator engages with the viewers, offering to help them explore the location. As the text keeps contradicting itself, the historical narrative turns out to be an empty construct of nostalgia, and demonstrates how the horizon can function both as a promise, a future to be obtained, but also as a prison, a border that cannot be traversed.

ANTE mag. You were recently included in the 2020 Immigrant Artist Biennial (TIAB). Can you tell us more about your work on view in this exhibition at EFA?

RN. For TIAB, I was included in the exhibition “Mother Tongue” which was curated by Katya Grokhovsky, Mary Annunziata, Allison Cannella and Anna Mikaela Ekstrand. I had the opportunity to show the first two parts of an ongoing media installation project titled Temporarily Removed.

The videos were shot in historical and ethnographic museums in NYC and Israel (where I’m from). Each video brings together two locations to examine how national narratives are produced through these institutions, and what is missing, hidden, or purposefully removed from the display in order to cultivate a sense of belonging or exclusion and reinforces the dominant national narrative by jumping between eras, continents, and modes of consciousness.

“Daydreaming” was shot at the Rockefeller Museum in East Jerusalem (formerly the Palestinian Archeology Museum) and at the Met Cloisters. The video follows the daydreams of a statue as it contemplates its life choices and possible futures by daydreaming of other places.

“Weaponizing Vulnerability” brings together artifacts from The Prehistoric Man Museum in Kibbutz Maayan Baruch, Israel, and the Museum of Natural History, NYC. I use these artifacts to ask the viewers questions regarding the different ways in which cultures touch each other, how these relations reflect the power imbalance between these societies, the meaning of freedom and the possibility of escape.

ANTE mag. What are you looking forward to in 2021 in your studio?

RN. I am currently working on a video-installation titled “Mouth Full of Water.” The work revolves around conversations I had with fellow immigrants since the beginning of the pandemic regarding protests, visibility, limits of expression, and the desire to take action. In our conversations, we often discussed the gap between the understanding and experience of a political system as an outsider and insider, and how the experience from one place can inform the potential for action in the other, or serve as a warning sign for where we can end up.

For this project I combine sculptural elements and digital manipulations creating hybrid spaces that allude to ethnographic displays (the artist Milcah Bassel created the suminagashi prints I use in the video). The title, “Mouth Full of Water,” is a play on the Hebrew saying “filled their mouth with water,” which means that someone is choosing to remain quiet about an issue. In this case, my protagonist’s mouths are full of water not by choice, as participating in protests here can endanger their visa status here in the US.

Another project in the making is a drawing and sculpture series, which a friend described as a “bodily alphabet.” The figures create a transformative dance trying to maintain equilibrium, shapeshifting to support each other. I’m still experimenting with materiality and scale and I’m excited to see where I’ll end up.

Lives and works in New York, NY and Long Island, NY

ANTE mag. Your work was recently featured in a debut exhibition at Public Swim, Not in My Backyard and with Quarantine Quotidien at Cristin Tierney. Can you talk to us about the works you exhibited in each show?

MO. The Public Swim exhibition included paintings I created about suburban homes, pruned trees and barbecues that have a playful mix of figuration and abstraction. Curators Madeleine Mermall and Catherine Fenton Bernath created a suburban backyard setting within their gallery down in the Two Bridges neighborhood, complete with lawn chairs and astroturf. It was incredibly light and joyful but sadly fell on the eve of the mid-March 2020 lockdown. Mixing my paintings of these mundane suburban rituals with the sculptures by Meryl Bennett and Sarah Hughes the exhibition became an installation unto itself totally departing from the white box gallery.

One of my paintings was that of a large lemon tree that lives in a forgotten corner of my mother-in-law’s backyard in Santa Monica, and I was invited to continue the painting onto the wall of the gallery. I have always been interested in this tree because it is entirely neglected yet in the California sun it grows wildly. It has been hacked back repeatedly to slow it from getting to someone’s idea of ‘out of control’. As a result it grows at an awkward slant like it is injured and crouching. I love this tree, I love its deformity and it captures so much about how we treat the natural world and how it rebounds.

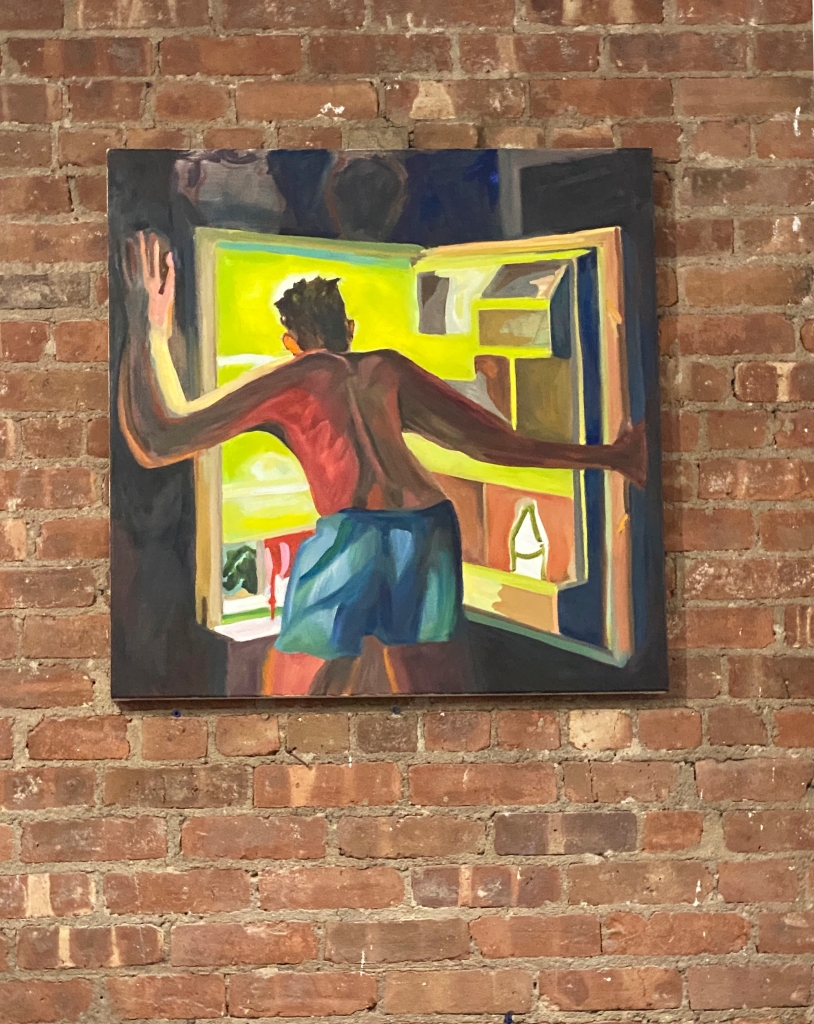

My paintings in the exhibition also included those of barbecues, which depict a ritual that is an explosion of color and light but embodies a contradiction: safety of a controlled burn yet an indulgence of our most primal urges. There were also a number of my paintings of ordinary houses from the 1970s that are strung out across middle class Long Island neighborhoods. As a painting motif when these houses are in light they break apart into abstract graphical problems as blocks of pure color and form. The paintings are a reflection on their privacy, modesty and individual personalities.The Cristin Tierney exhibition (visible now in their viewing room) got out of the gate early to capture what the pandemic felt like when we were just a few months into it. I found myself focused on the inner workings of my house, on the little of my neighbors that I could see from my windows, and on the anonymity of driving on the road when out on a rare errand out. My paintings depicted routine activities like midnight snacks, cleaning the yard alone and, especially, watching someone drive away, how that creates a sadness even if you don’t know the person. The painting of the man looking for food in the refrigerator, with urgency and panic, is about the feeling that you know you don’t have something and can’t get it. He is swallowed by the light of the appliance and an outline drawing of the milk carton imparts a sense of emptiness.

ANTE mag. As a painter, have you faced specific challenges in producing new work during the pandemic or has this proven an opportunity for you to create new bodies of work in your studio?

MO. I think many painters are used to spending time alone and even gravitate to a somewhat monastic existence. I certainly do and this mitigates the impact of a lockdown. But I have been lucky to have been healthy and to have had access to my studio during the entire pandemic and to have been able to get supplies. It has actually been a really productive time for me even though I think daily about how people are suffering and of my friends who have tested positive or gotten sick.

Being limited to pixels to connect to the outside world does take its toll. I greatly miss being able to visit museums and exhibitions to take in the materiality of other work by other painters, their surfaces, things as simple as how thickly or thinly they applied paint. And to speak to curators, writers and other artists in person, not to mention friends and family.

ANTE mag. Your recent works often approximate the human presence within the built environment (landscapes featuring apartment blocks, for example) or are explicitly portraits. Can you talk about the dichotomy between these two themes in your work and/or the similarities in process that are shared across these two different themes?

MO. When painting a portrait I always hope that the person will sit in an integrated way within his or her surroundings and I like to pick an object to show with them that somehow speaks to their idiosyncrasies. The similarity in process to depicting the built environment is that all painting problems for me reduce to light on form and the tension between verisimilitude and the look of the paint on canvas itself. We live in a world so dominated by perfect things and images made by machines that I think it is also important to see the hand of the artist in a painting, even as mistakes. It creates a human connection with the viewer about what it means to touch.

Whether in a work about the built environment or a portrait, I create paintings as someone might write in a diary: essentially putting down my shifting preoccupations and responses to what I encounter. I like imperfection, I feel it is very human. For a portrait, I try to step back and think what do I feel about this person, what flaw or charm has drawn me to them. Likewise for the built environment, the barbecues, or suburban houses or pruned trees that I paint, they are a record of how people interacted with the natural world, more often producing mistakes or showing their fragility than creating new beauty.

ANTE mag. What are you looking forward to in 2021 in your studio?

MO. I am really excited about finalizing the work for an upcoming solo exhibition at the Custom House in Mayo in western Ireland. It will be about how modest American homes are a metaphor for the Irish diaspora. As a second generation Irish American, immigration is a very much a part of my life, my mother was born in Dublin and I am dual citizen of the US and EU. This is my first chance to put together an exhibition that grows out of being an Irish American.

I am also focused on group portraiture and family portraiture, something I experimented with for the American Wilderness exhibition in Japan in late 2019. When you have multiple people in a painting the dynamic of how they relate to each other can be quite charged. I’m interested in exploring that while also keeping alive an interplay between the abstraction and figuration of their surroundings. Also, a part of my practice includes photography and I have a second book of photographs coming out in 2021. It will be published by the Midwest Center for Photography and is about the aesthetics of civic structures, structures that we have created as a society and how they make us feel. In the photographs I am looking for beauty in mundane aspects of bureaucracy where it would seem most unlikely to find beauty.